The Monument to Joe Louis, known also as "The Fist" in downtown Detroit. The city filed the biggest municipal bankruptcy in U.S. history on Thursday.

Ryan J. Stanton | AnnArbor.com

- Related stories: See MLive.com's coverage of Detroit's bankruptcy

News that the City of Detroit filed the biggest municipal bankruptcy in U.S. history on Thursday sent shockwaves throughout Michigan.

For some, the move by Detroit’s state-appointed emergency manager Kevyn Orr was necessary to help the long-troubled city climb out of its multibillion-dollar debt and pave the way for reinvention. Others believe that the bankruptcy, which could cut pension benefits to city workers and retirees and leave bondholders with pennies on the dollar, will go down as a dark moment in the city’s history.

On Friday afternoon, the status of the bankruptcy was uncertain after an Ingham County judge ruled Thursday's filing unconstitutional. Initial reports indicate the judge says the filing was rushed.

Yet, now that Orr's intent to pursue bankruptcy is clear, community and business leaders 45 miles west of downtown Detroit are surveying the landscape. Washtenaw County is trying to determine what the bankruptcy will mean for the future of Detroit, southeast Michigan and the state.

“The notion that we’re separated from Detroit is flawed,” said Albert Berriz, CEO of Ann Arbor-based real estate company McKinley.

“The real estate values in Washtenaw County decline geometrically as you go east, not surprisingly,” he continued. “If you don’t think the city of Detroit and Wayne County have an adverse effect on real estate values, you’ve got your head in the sand. A stronger Detroit and a stronger Wayne County result in a stronger Willow Run and a stronger Ypsilanti.”

A major concern among local elected officials is how Detroit's bankruptcy might affect the municipal bond market and local governments' ability to borrow money to finance major projects.

Washtenaw County Commissioner Conan Smith, executive director of the Michigan Suburbs Alliance, said that what is unfolding in Detroit is complex, and it's difficult to say at this point what the long-term implications might be for the region and the state.

With Detroit possibly owing $18 billion or more in debts, it's expected there will be a fight among more than 100,000 creditors over who will get paid — most at risk are those holding $11 billion in unsecured debt.

Smith said it's a risky move on the state's part to classify hundreds of millions of dollars in general obligation bonds as unsecured debt. He fears that could result in higher borrowing costs for other municipalities in Michigan, not just Detroit.

Local governments like the city of Ann Arbor and Washtenaw County use general obligation bonds to finance major capital projects like new buildings and parking garages.

"The state is in charge of the City of Detroit right now, and they made this bankruptcy decision, and they've chosen not to pay these general obligation bonds," Smith said. "That has the serious potential to disrupt the general obligation bond market for every locality in the state of Michigan."

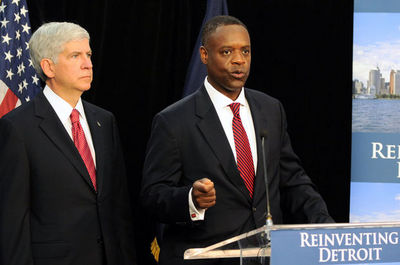

Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder and Detroit’s state-appointed emergency manager Kevyn Orr.

MLive.com

Smith said there are already people speculating there will be a premium placed on Michigan bonds in the future, and that “we'll pay a higher amount just because we're from Michigan." But he doesn't think there will be dramatic impacts in Washtenaw County.

"We have a AA bond rating, we're very financially secure, and we're seeing strong growth in our tax base," he said. "It may affect us in terms of the expense of borrowing money, but it's not going to stop us from doing the things we need to do."

Ann Arbor Mayor John Hieftje said he's been listening to what the financial experts have to say about what could happen to the municipal bond market.

"There's been some speculation about that, but we are very hopeful Ann Arbor will be in fine shape because our bond rating has actually been improving over the years and we're in a very strong financial position," he said. "We can't predict what will happen overall, but we hope any fallout from that doesn't affect Ann Arbor and other cities that are strong."

Tom Crawford, the city of Ann Arbor's chief financial officer, said he's viewing the bankruptcy as a Detroit-specific issue and not anticipating a local impact yet.

"However, we are watching it, because this is only one step in a process that really goes through the courts," he said. "There are a number of legal questions that come up in going through that process, and the result of those legal decisions may or may not have an impact on us locally, so we're still in a position of wait-and-see just as we have been for the last six months."

Smith noted there are tens of thousands of Washtenaw County residents who are part of the Detroit water and sewer system and he's not sure if there will be implications for their services.

For the entrepreneurial ecosystems of Ann Arbor and Detroit, the bankruptcy could test a relationship that has have been strengthening over the past few years.

“I sincerely hope that [the bankruptcy] won’t discourage the increased connectivity we’ve been seeing between our startup communities,” said Adrian Fortino, who lives in Ann Arbor and now works as a vice president for Invest Detroit.

“I hope people still see that there are great things happening in Detroit. There is great potential here and great opportunity. We’re certainly not going to stop building that bridge.”

Fortino, who started multiple companies in Ann Arbor, said that filing could end up have a solidifying effect by creating an "it's up to us" mentality.

“The city's problems are not going to stop us from getting together as entrepreneurs and investors to work on our ideas and our businesses,” he said. “It creates a level of uncertainty with regard to the city, but it won’t stop us from moving forward.”

From a real estate investment standpoint, Stewart Beal of Ann Arbor-based JC Beal Construction is hopeful the bankruptcy can “right the ship” and lead to further development in the city of Detroit.

Berriz agreed, adding: “I think from a business view, in terms of political certainty and people wanting to invest in Detroit, this is a watershed moment.”

Beal said JC Beal Construction, which operates an office in Detroit and has completed many projects within the city boundaries, swore off working directly with the city last year.

“We are fully invested in doing business in the city of Detroit, just not with the City of Detroit, because it has been so abusive in the past,” Beal said.

He cited several examples of the city hiring JC Beal Construction for projects — including an $800,000 contract to demolish 100 homes in 2011 — but then failing to pay until months after the projects were completed.

“I was owed over $400,000 for over eight months before (the city) finally paid. It really hurt us. It hurt the people that were my employees, it hurt my contractors, and it hurt my subcontractors because I couldn’t pay them since I wasn’t paid.”

Beal doesn’t believe Washtenaw County will feel the direct impact of Detroit’s bankruptcy — at least not in terms of real estate investment and business activity.

“I think people have known about this for so long that all of the market reactions to this have already occurred,” Beal said. “Ten years ago, when I started buying properties in the City of Ypsilanti, I knew that was 25 minutes from Detroit, and I already weighed that in my investment decision.”

But former Ann Arbor Chamber of Commerce president and Ann Arbor Transit Authority chairman Jesse Bernstein, is worried Detroit’s reputation could take a major hit in the wake of the filing, dragging the region down with it.

“I can’t even begin to imagine what the impact will be on southeast Michigan,” he said.

“If nothing else, if everything works out financially, this is a huge stain on Detroit and Michigan Who knows what impact that will have on tourism and whether people will want to come to conventions or meetings or even move here.”

Bernstein is also worried about what effect the filing could have on the AATA. He said that with the regional transit authority overseeing state and federal funding, he’s concerned that money that previously would have gone to Ann Arbor could instead be re-routed to the Detroit Department of Transportation bus system.

AATA CEO Michael Ford said via email that the information is new and it’s premature to speculate on the impact it could have on the transportation authority’s finances.

Lizzy Alfs is a business reporter for AnnArbor.com. Reach her at 734-623-2584 or email her at lizzyalfs@annarbor.com. Follow her on Twitter at http://twitter.com/lizzyalfs.