Clik here to view.

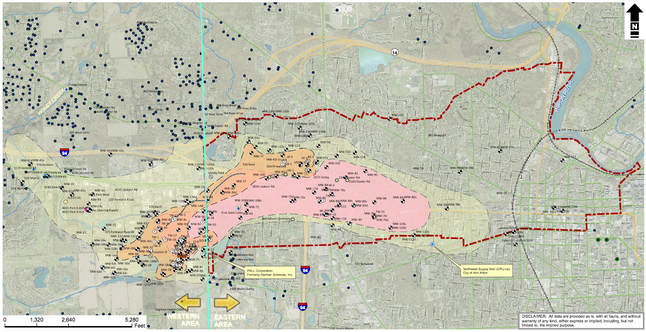

This map produced by the Environmental Health Division of the Washtenaw County Department of Public Health shows the latest estimation of the footprint of the Pall-Gelman 1,4-dioxane plume. Local officials say the contamination is spreading through a system of underground streams, contaminating the groundwater in those areas. Download larger version.

Courtesy of Washtenaw County Department of Public Health

By a 9-0 vote, the City Council approved a resolution that urges the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality to use the best science available about 1,4-dioxane to set stricter cleanup criteria for the cancerous pollutant found in the groundwater on the city's west side.

"It is way overdue that the DEQ do something," said Mayor John Hieftje, who joined Council Members Sabra Briere and Chuck Warpehoski in sponsoring the resolution.

Based on a toxicological review from 2010, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency now thinks dioxane is even more cancerous than previously believed.

Clik here to view.

John Hieftje

The state DEQ for the last several years has enforced a cleanup standard of 85 parts per billion, which is intended to result a 1 in 100,000 residual cancer risk.

Ann Arbor officials want to see the Pall-Gelman dioxane plume that's creeping further into the city's groundwater from Scio Township cleaned up to a higher standard before it hits the Huron River.

Gelman Sciences, which later became Pall Life Sciences, used the industrial solvent 1,4-dioxane in its processes for the manufacture of medical filters on Wagner Road many years ago.

Between 1966 and 1986, wastewater containing the toxic chemical was sprayed on its lawns and stored in unlined lagoons. The dioxane seeped through soil and rock layers into the groundwater and began to spread, leaving parts of the city and Scio and Ann Arbor townships contaminated.

Environmental monitoring and remediation efforts are ongoing and are being tracked by the DEQ, even as Pall announced this year it is closing its business operations here.

Roger Rayle, leader of a group called Scio Residents for Safe Water, spoke in support of the council's resolution at Tuesday's meeting.

"The DEQ has been dragging its feet on this for more than two years and they're acting like they're never going to tighten the standards," he said.

"I'll remind everyone that in 1995, when the standards were loosened under the guise of cleaning up urban brownfields, the standards were changed basically overnight to the benefit of the polluters."

The council's resolution notes the DEQ missed its self-imposed deadline of December 2012 to set new cleanup criteria based on the EPA toxicological review.

The DEQ's deadline for revising the criteria was extended until Dec. 31, 2013, but city officials said it appears unlikely even that deadline will be met now.

Sybil Kolon, the DEQ's project manager for the Pall-Gelman plume site since 1995, cited a lack of consensus between the regulated community and environmental health officials as one reason for the delay in adopting new cleanup criteria for dioxane.

"That got put off until this December and there's supposed to be a public process related to that," she said. "I'm hopeful that we're going to get news on that in the next week or so."

Council members expressed concerns Tuesday night that they still see the plume spreading, and they don't believe the most effective cleanup methods are being used. They're particularly worried what might happen if the contamination spreads to the Huron River.

About 85 percent of the city's drinking water comes from an intake pipe at Barton Pond on the Huron River, while 15 percent comes from wells located at the city's airport. The city already had to shut off a well station on the west side of the city about a decade ago because of the plume.

Given the rate the plume has moved since it first developed decades ago, Briere said, it could be 20-plus years before it gets to Barton Pond — if it even heads in that direction.

Some believe it will hit the Allen Creek before that happens and be channeled to the Huron River at a point beyond the city's drinking water supply intake. At that point, the dioxane concentrations would be diluted, Kolon said, and there are no drinking water intakes downstream from Barton.

Council Member Stephen Kunselman, D-3rd Ward, said the dioxane plume issue has dragged on for a long time and he's not inclined to rely on the DEQ or the EPA.

He wondered what the city could do on its own — as a future contingency plan — to protect its primary drinking water source if the dioxane plume makes it to Barton Pond.

"That's the question that we need to address," he said. "I don't know if we have the wherewithal to do something like pump out Barton Pond and refill it with something else.

"But what would we do? Would we have to take it upon ourselves to filter out the dioxane before we pump water to our residents?"

He pondered whether the city might connect to the Detroit water system if Ann Arbor's drinking water supply became contaminated with dioxane.

Hieftje said he'd like to see a broader community conversation happen to address some of the longer-term concerns. He stressed there's no imminent threat to the city's water supply.

But he said he's been concerned about the dioxane issue since before he became involved in city government in 1999, and he's glad the city is pushing for action in Lansing.

"Our consultant in Lansing has been working pretty hard on this issue for quite a long time and has been working very hard this past year to keep it in front of the DEQ," he said, adding Tuesday night's unanimous resolution gives the city's consultant "a little more to work with."

Matt Naud, the city's environmental coordinator, said he's been working on the issue since the fall of 2001. Changing the statewide cleanup standards for dioxane, he said, would radically change the attention given to the Pall-Gelman plume.

Naud said the city is keeping tabs on dioxane levels in the groundwater below Ann Arbor using data from probably a couple hundred monitoring wells.

He said the city has never detected dioxane in Barton Pond. Pall also tests for dioxane where the Honey Creek meets the Huron River, Naud said, noting that will give the city an alert if there ever is an issue with contaminated water heading downstream.

Kolon, who lives in Manchester Township, said she believes public health and the environment are being protected, even though the plume is expanding further into Ann Arbor.

"We are well aware that some of the citizens have concerns about future exposure risks, including the Barton Pond issue," she said, suggesting adequate monitoring is in place to detect if the plume is moving in that direction well before it becomes a risk to the public.

"The spreading toxic plume is not a surprise," she added. "The plume is migrating, but the company has to track it and address it if it's going outside the areas where people could be exposed. There is a little bit of concern to the south and we're watching that very carefully."

But at this point, she said, there's no evidence any concentrations above 85 ppb have migrated out of the zone where groundwater use is prohibited.

Naud lamented that the DEQ allowed Pall to change its cleanup methods. Pall is now using an ozone-oxidation process to remove dioxane from water that's extracted from the ground in the plume area and then discharged to the Honey Creek.

"The DEQ allowed them to change their treatment technology and it actually puts more 1,4-dioxane and an additional carcinogen in the water instead of what they did before," Naud said.

Pall's official position has been that it's in full compliance with a consent judgment the company entered with the DEQ, which serves as the legal framework for the cleanup, and the ozone-oxidation treatment technology it's using has been approved by the state.

Bromate is a byproduct of the treatment process. Kolon said it's not allowed to be in the water Pall is discharging at greater than 10 ppb.

According to publicly available reports, Pall removed roughly 640 pounds of dioxane in the first half of this year by extracting 150 million gallons of groundwater, treating it using an ozone-oxidation process, and discharging the remaining water into the Honey Creek.

Since May 1997, when major cleanup activities started, nearly 90,000 pounds of dioxane have been removed and roughly 6.8 billion gallons of water treated and discharged.

"Based on our current law and the consent judgment, we can only do what is required under the law and we think that is being met," Kolon said. "We understand that the community doesn't want any dioxane in its water, but unfortunately that's not the standard we're able to enforce.

"That's certainly not an imminent threat," she added. "I think they're using very good technology. Could they do more? Of course."

Jane Lumm and Marcia Higgins were absent Tuesday.

Ryan J. Stanton covers government and politics for AnnArbor.com. Reach him at ryanstanton@annarbor.com or 734-623-2529. You also can follow him on Twitter or subscribe to AnnArbor.com's email newsletters.